While such an understanding, as equally her No-Manifesto seemed to concern mostly dance and art, it was meant to change in quite profound ways, not only how we perceive movement in dance, but consequently ourselves. There is an episode in the new film of Jack Walsh about Rainer where she recounts how she convinced in 1960 the senior minister Howard Moody of Judson Memorial Church to open the space to dance with a performance of ‘Three Satie Spoons‘. Accordingly he said afterwards: “I don’t understand it, but it feels important.”

Feelings are facts is the title of Yvonne Rainer’s memoir published in 2006, and the line now also became the title of this documentary about her work and life. The film had its first public viewings at the recent Berlin Berlinale. The following clip shows an interview with the filmmaker and the producer, who were present for Q&A after each screening.

Interview with filmmaker Jack Walsh and

producer Christine Murray at the Berlinale 2015 (link)

As critically mentioned at the questioning I attended and also in some reviews of the film it is a sort of conventional ‘talking head’ documentary mostly based on interviews with like Steve Paxton, Cat Patterson, Simone Forti, Carolee Schneemann, B. Ruby Rich and others.

In 1999 I had a chance for a stop-over in New York City. It was my first visit to the town, and due to my teacher of that time, performance artist Joan Jonas, I had developed some interest for the NYC art avantgarde of 60s and 70s. By accident I came across the announcement for a free performance evening at Judson Memorial Church. Without knowing too much about Rainer or Judson, I was stunned about the long queue that had already been formed around one corner of the church on my arrival. At that point the feeling that I might be attending something special started to grow. While watching the dancers I noticed J. Jonas in the audience and she later told me that it indeed has been a really rare performance. Something I certainly know by now as it was Trio A Pressured performed on October 4, 1999, at Judson Church by Pat Catterson, Y.R., Douglas Dunn, Steve Paxton, and Colin Beatty (list of ‘Trio A’performances) and eventually let to Rainer’s engagement with Baryschnikov, which marks her return to dance after about 15 years devoting herself to film making.

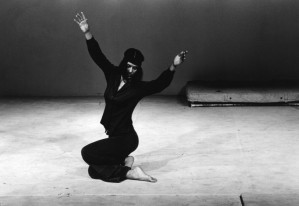

Yvonne Rainer, Trio A, 1978 (link)

Walsh’s film begins with a digitally reworked recording of ‘Trio A’ for once good enough for cinema screen. Though a bit into the film Rainer mentions that this version of the dance, recorded in 1978, which is the only early existing recording of the full cycle, is not regarded by her as the most accurate performance of it she ever has done.

It is amazing to see her speak and get a sense for the preciseness she expresses in both thinking and moving. Suddenly ‘Trio A’, this obscure and at its time disturbing piece of sequences of movements, becomes one of the clearest and thought through pieces one might ever have had a chance to watch. So at its time it has been that much unanticipated that even Steve Paxton, one of her close colleges at Judson Church in the 1960s, says: ‘I have never understood it,’ though he has performed it many times and is one of the people, who has it as a knowledge in his body. (see Berlinale excerpt)

Interestingly Cat Patterson, dancer, choreographer, and permanent participant in Rainer’s works has quite an interpretation of her own, as she recalls, that the most fascinating aspect when seeing ‘Trio A’ for the first time, was to see someone as absorbed as ‘in folding laundry’, in pure activity, as being without audience. In an essay published in 2014 she lays out: “There are stylistic elements and aesthetic preferences in Yvonne’s work to attend to as well. As in her early work, characterized as epitomizing the notion of “the neutral doer,†she prefers an unadorned, direct performance of movement, with a weighted ease more pedestrian- or athletic-looking than technical.”

Y. Rainer herself defines ‘Trio A’ as a kind of lexicon of movement possibilities. And it is eventually the dancer Emily Coates, belonging to a younger generation that keeps the dance alive by literally embodying it through having it in her repertoire, who comes the closest to its meanings in current times by expressing that ‘Trio A is theory in motion’. A point that becomes obvious towards the end of the film when Rainer explains aspects of her interest in movement and the methods she uses for working on new pieces.

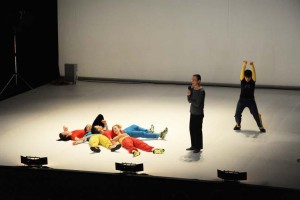

2011, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2012 (link)

Instead there is some focusing on the not unimportant circumstances of the times like getting grants or being refused, as well as on the cheap housing of that time (but be aware 20$ in 1963 had the same buying power as $150 today) and by that some of the statements remain at loose ends. For example when Rainer states that by knowing she won’t get more funding for her Murder – MURDER film project, she decided then to start and “let it run”. It would be interesting, what this ‘let it be running’ means, as Rainer expresses in her appearance and work certainly that she wants to have things put in a very specific way. She explains in an interview with D. Crimp: “I am interested in how things don’t work, putting things together that don’t fit.”

Throughout her rich oeuvre in dance, film and theory it is a sort of ‘felt fact’ that the mind-muscle-feeling-facts equation is a run-through thread allowing to bring these seemingly disparate elements together. Cat Patterson gets to the heart of this provoking juxtaposition when she states: “One needs as much mental as physical alertness and absorption, and the challenge is to not let the mental effort increase the body’s tension.” And this is still an everyday challenge equally for the ‘neutral doer’, as for the acclaimed artist.