| “It takes a long time to become young.” said Picasso. And I think he meant the curious look, the undoing of the known, the ability to comprehend outside the rule and to try instead to open up an inner space that unsettles the framing view. Letting go the preformed seems to be a tough task after all that careful education within confined cultural norms of our various societies. Too often we confuse the learning of a certain method with the thought that a subject could ever be understood in its entirety.

The exhibition “Found in translation†accents the ways language creates a crucial component in how we communicate ourselves across the borders of the limited canon of the available expressions. The works show how interaction can be used to cross the gaps of translation or transposition. From street signs to book illustrations, image based narration is certainly one of the most widely spread tools to communicate all over the world. Though many of the exhibited works stick close to the title and focus on acts of speaking while using video as a real-time tool to address the elusiveness of the subject. The moving image certainly is omnipresent via TV or internet in today’s world. But the power of the still image combined with text yet has its place. From ads to instructive illustrations it occupies the landscape of our daily movements. And not to forget our beloved comic books which always have been anticipated to open up fantastic worlds of thought and imagination. The more interesting though is the approach of the artist Siemon Allen who not only uses a classical European childhood comic to decipher the embedded historical cultural presets, but also does this in a strictly young and visual way. |

|

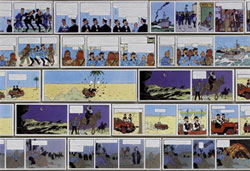

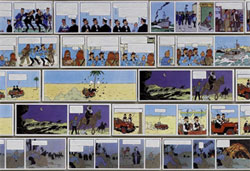

| ‘The Land of the Black Gold’, first published 1939/40 as supplement of a Belgian newspaper is one of the early issues of Hergé’s comic series ‘The Adventures of Tintin‘. The story is located in a Middle East that was originally set in the British Mandate of Palestine referencing the then actual conflicts between residing Arabs, the colonist British Mandate and Zionist Jews. For the English edition published in 1972 Hergé had to redraw and rewrite significant parts. |  |

| Relocating the storyline in the fictional kingdom of Khemed obliterated all political references and turned the comic strip into an exemplary reference to Western Orientalism and the blurring of a colonial past.

Allen’s method is obvious, extensive and effective. He erases the text in the speech balloons of the entire comic leaving blank areas in the upper third of most of the images. Then he aligns two different editions of the same comic, the 1950 version and the re-edit from 1972, in 5m long image strips running in parallel horizontal lines across the wall. As the shifting frames of the image rows fall out of sync, they reveal through their increasing mismatch a visual mutation. More persuasive than any literal explanation this discloses the indication of an uncanny look onto the developments in the region, and how the ’accepted‘ point of view, the understanding of ’political correctness‘, the ’adult view‘ – in all its connotations of being superordinate – influenced the angle of narration and at the same time defined that world and the story told. These reductive methods visualize an ambiguity that indicates how history might be re-written or altered according temporary needs. The employed tools are relatively simple. It is about stripping down the common reading, sweeping the speech bubbles as a kid might do. An almost unintended unfolding of a different perspective occurs that allows to grasp a veiled kernel. Similar to what Picasso had suggested: a young – yet unlearned perspective appears. Siemon Allen |

|